Recent reports that deaths from terrorism are significantly down do not seem to apply to Africa.

A few weeks ago I helped to organise the first ever Canada-based launch of the annual Global Terrorism Index, as it is compiled by the Australian Institute for Economics and Peace, at the University of Ottawa, where I am the Director of Security, Economics and Technology.

The most salient message coming out of this 7th report was a rare happy one. Deaths arising from acts of terrorism in 2018 were down 15.2 percent from the previous year. Furthermore, terrorists deaths have decreased 52 percent from 2014. These are amazing figures and we should feel good about this.

None of this suggests that terrorism no longer poses a threat that must be fought and, if possible, contained or even eliminated (I have to confess that even on my most optimistic days I cannot imagine the ‘elimination’ of terrorism). But for a phenomenon which has garnered so much attention, especially since 2001, any trends pointing in the ‘right’ direction are good ones.

There do appear to be exceptions, however.

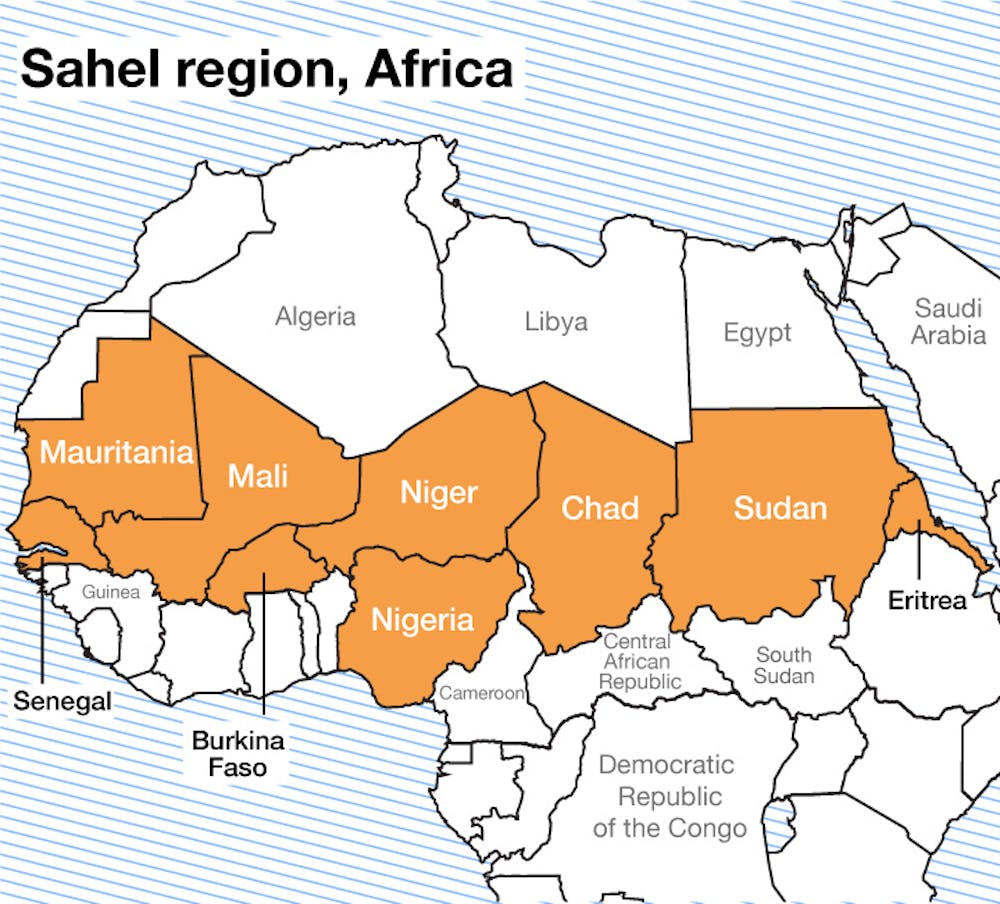

According to a story on the BBC Website a few days ago (December 22), France appears to be losing ground to terrorists in the West Africa, an area defined as part Sahel and part West Africa proper. France has been trying to coordinate counter terrorism action in the region since 2014 and has helped to create what is known as the ‘G5’, a grouping of Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger.

Casualties from terrorist groups are on the rise in several countries, especially Niger (see chart below). Similarly, in Mali, a counter-insurgency operation, launched in 2014 and supported by French forces, has proved largely ineffective in its efforts to tackle widespread insecurity. Burkina Faso – a country previously less prone to jihadists attacks – has also experienced an upsurge in terrorist deaths (see second chart below).

There are simply far too many jihadi groups operating in the Sahel. Among the most important, and the most lethal, are:

- Jamaat Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) – an alliance of jihadist groups, active throughout the Sahel region

- The Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) – affiliated to ISIS, active in north-east Mali

- Ansarul Islam – active in northern Burkina Faso

- Boko Haram – present in north-eastern Nigeria, Niger, Chad and northern Cameroon

In other words, both Al Qaeda (AQ) and Islamic State (ISIS) have their claws into local groups. This is not good and the forecast for the Sahel is not sunny: expect more terrorism fronts to make their way to the region.

Contrary to France’s ongoing commitment to its former colonies in Africa, according to the New York Times the US is weighing proposals for a major reduction — or even a complete pullout — of its forces from West Africa as the first phase of reviewing global deployments that could reshuffle thousands of troops around the world.

The primary mission of the American troops has been to train and assist West African security forces to try to suppress Islamist groups like Boko Haram and offshoots of AQ and ISIS. It appears that this mission is under scrutiny as the Pentagon has assessed that none of these groups have the capacity or intent to hit the US.

Maybe. On the other hand I am sure no one thought a guy named Usama bin Laden and his merry band of AQ jihadis had the similar capacity or intent to hit the US either. Then we got 9/11.

I am of two minds on all this.

I have long argued that seeing counter terrorism as a ‘war’, largely fought by our militaries, is a mistake. No war against a common noun, of which terrorism is one, ever really ends. Poverty? No. Drugs? Nope. Crime? Zilch. (By the way, the single best essay on why wars on common nouns is a bad idea was a piece written by Grenville Byford published in Foreign Affairs in 2002)

At the same time, without outside assistance there is little to no chance that the aforementioned nations can ‘defeat’ the panoply of terrorist groups active on their soil.

At the same time, without outside assistance there is little to no chance that the aforementioned nations can ‘defeat’ the panoply of terrorist groups active on their soil. The military forces of these countries are either not strong enough or not well enough trained to carry out counter terrorism operations without also engaging in human rights abuses, which in themselves sow the seeds for more terrorism down the road.

In the end I think we are damned if we do and damned if we don’t. There is no simple answer to the question of how involved the military should be in battling terrorism. Anyone who tells you s/he has the right formula is lying.

I think we will have to muddle through as we do on most things. Let’s just hope we don’t make things worse.